|

|

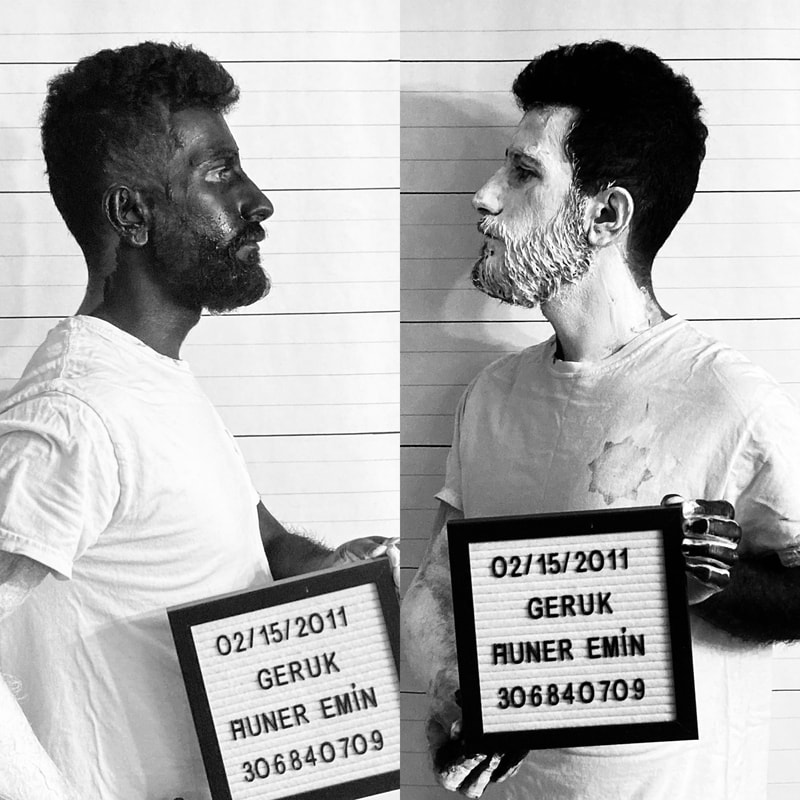

I am a stateless Kurdish artist from south Kurdistan/northern Iraq, living and working in Indiana, USA. I grew up in Iraqi Kurdistan, studied Academic art in Erbil, and moved to The United States to study MFA in art painting in 2013. Since I left my country, I have never returned due to my political issues with the Kurdish Reginal government of Iraq. During the Arab Spring, I performed an art piece called Geruk, questioning the power and the political dogma that caused my arrest by authorities in northern Iraq. I tend to create an art bridge between different art-making philosophies by reflecting on Middle Eastern and Western cultures. I studied western classical art in Iraq, where I learned to create art that resembles Western culture's horizontal perspective and visual aesthetics. Meanwhile, my art practices developed during my MFA study in the United States, where I worked on subject matters that reflect my country of origin's political and social issues. I sought authenticity in my work and established a system descended from the verticality and poetic nature of the middle east culture. The nature of my work is storytelling expressed by calligraphy or visual symbols containing various subject matters such as honor killing, genocide, or suppression. I reorganize and reform shapes and materials to create art pieces of multiple media styles, video art, installations, and paintings.

The Interview

At what point in your life did you know that you wanted to become an artist? Did the realization emerge slowly?

I jokingly used to say that I have an arranged marriage with art. I grew up in northern Iraq or the Kurdistan Region, and everyone wanted to be a doctor, teacher, or lawyer. I, however, wanted to be a journalist. In my teenage years, I was heavily invested in writing poetry and wanted to build the courage to evolve it into journalism. The arranged marriage with art happened after my high school diploma score was not high enough to secure a journalism college seat (there was only one school in the whole region). My degree put me in the last choice of the list of universities, Sulaymaniyah (the art school), in the west side of the country, in a city opposite to my eastern city Duhok, both in terms of spoken Kurdish dialect and a different dominant political party.

Of course, getting into an art college like Sulaymaniyah University was not easy. It is a highly regarded college where many students trained under the teaching of the first Iraqi pioneer artists who were teaching at the Sulaymaniyah College of Art. The visual, academic, and practical skills needed to enroll in the program attract top-notch students. Graduates have created a solid visual culture in the Kurdistan Region.

After a practical and theoretical test, I was accepted in 2006. My visual art skills rescued me – a talent I acquired and developed from imitating my amateur poet and artist uncle. Perhaps he was my inspiration to get into art school. I knew I had visual skills in childhood, which were displaced for writing poetry in teenagerhood. I remember my teachers were impressed by my visual skills in drawing the Iraqi map with all the rivers and cities from my memory. After acceptance into the art program, I began practicing drawing, painting, and sculpting. There is probably a reason I lean toward creating investigative art, perhaps my journalism interest. After all, there is a connection between the art I make and the field of journalism. So, the realization of becoming an artist was slowly dependent on nurturing my artistic skills through my childhood and the environment that I grew up in, where I didn’t control the turn of events.

How did you evolve your style and favorite mediums?

The story of how my style of artmaking evolved is quite interesting. Of course, at an early age in studying art, every artist is influenced by a movement of art or a mentor. For me, it was my extraordinarily talented and intelligent professor Namo Rustamzada at my bachelor’s degree in Iraq. Namo was and still is the best influencer of my artistic career. We would sit in his experimental painting class, and he would translate Omar Khayam’s poems from Farsi to Kurdish for us. He encouraged us to feel for the objects we were making rather than thinking, almost like making art with our hearts rather than our minds. Despite having incredible classical painting and drawing skills, Professor Namo also introduced performance art, installation, and conceptual art to us.

Namo’s influence opened my eyes to art’s route in the western world. When I was in Kurdistan, I looked up to the west for the style of art I wanted to make. I was overwhelmed by the abstract expression movement and was doing performance art. In my opinion, up until then, I was imitating western art. I didn’t feel the authenticity in my paintings, even though my performance art tended to be more original. Geruk was a performance piece that I did during the Arab spring, and I was arrested while performing it. It challenged the power of religion and the political authorities in Iraq. My work stemmed from profound criticism of the Kurdistan region and the Iraqi political and social situation. At the time, I was looking up to western advancement in art, science, and technology.

The next step in finding my style was after I moved to the United States in 2013 and never returned to Iraq due to my political issue with the Kurdish regional government. After getting my MFA and familiarizing myself with the art scene, I returned to my origins and understood the weight of eastern culture. I began creating artworks that contain videos, as well as installations. Somehow, these new and investigative art pieces represent both the Eastern and Western worlds. In my mind, the video art stands for the eastern oral culture. Meanwhile, the installations stand for the western, predominantly materialistic, visual culture. It is a bridge I wanted to stretch between two cultures to reflect on my struggle, being transplanted and in exile.

What are your time management techniques? Do you have regular working hours...or favorite times to work?

I hate to say that I don’t have excellent time management techniques. I like to work at night when everyone is asleep. I feel full of emotions at night that I like to pour onto a canvas or paper when I write. I don’t want to be interrupted and distracted by my surroundings.

It is best when I cannot stop working; I believe I do better work then. There are periods of my life when I go through dry spells. Then there are times when I am flooded with ideas.

Do you work on more than one piece at a time, or primarily just on one?

Often, I find myself working on multiple pieces at the same time. Recently, I began working on a research type of art making, or I can call it investigative. They usually take much longer to execute, and during the process, I get hit by another idea for a different project, so I would go back and forth between them.

What would you say is your biggest influence--that which keeps you working, regardless of all else, your most steadfast motivation?

I mentioned earlier some of my influences. I am worried about the state of art today. We seem to have lost our beautiful knowledge of creating well-planned and effective art. We have begun to lose our expertise in creating art pieces as visually compelling as the classical masters. Much like the political system, we have replaced well-thought-out or planned artworks with temporary and experimental visual pieces. The art made now results from a system that seeks quick and easy solutions. I am worried that people’s visual and collective taste is decreasing.

I am not a traditionalist. I admire the new and different art, but I want it to be more profound and deliberate. Otherwise, we will lose our extensive visual heritage inherited from previous cultures.

What motivates me to continue making art is the art itself, the political system, and the culture we live in. I want a critical eye to point at the mistakes we collectively make in destroying the environment and suppressing the other. I want to make art that speaks for the collective and, in the meantime, criticizes the status quo of the human condition.

Does trying something new and not knowing the rules -- the boundary pushing -- create anxiety or excitement in you? (Or both?)

Moving into a new country was a new adventure for me. I prefer to be open-minded and learn the rules along the way rather than be restricted and stagnant. As a metaphor, I once told a friend to jump into the sea. I meant moving into a new country and different culture is like jumping into a body of water that you don’t know where the waves will take you. It is more struggling for survival than just excitement; as a refugee, it is interesting to contemplate the concept of the new and unknown.

Art is like that; every art piece is a new adventure that I don’t know how good of an art piece it will become. I like to plan and deliberately work on the subject matter. However, I love inspirational moments and crave them at times. I don’t think I am anxious when I make art.

Do you enjoy having the "duality of both chaos and control" or are you happiest with a set plan?

I prefer the balance between both. I want to be levelheaded in chaos and adventurous in set plans. I am not a by-the-book person, but I love finding reason in turmoil. My recent work is more planned than the “jump into the sea” kind of artmaking.

Do you have any projects or events forthcoming?

My most recent art project is about gun control. My wife and I are expecting our first child in December. I am trying to connect school shootings and bringing a child into this life. My piece will navigate the cruel life that children and adults endure in living in fear of a mass shooting. Simultaneously, I have a long-lived project in hand, working on the stories of ISIL victims of war. For the last five years, I have been researching ISIL victims and wanted to present their stories in artwork that is respectful to their experience without being theatrical in displaying the victim’s pain. It is perhaps my most significant project, and I would love to receive a residency or a grant to complete the project.

Blood Washing,

Oil colors on Latex lightboxes and video art, 2017

Oil colors on Latex lightboxes and video art, 2017

Blood Washing,

Oil colors on Latex lightboxes and video art, 2017

Oil colors on Latex lightboxes and video art, 2017

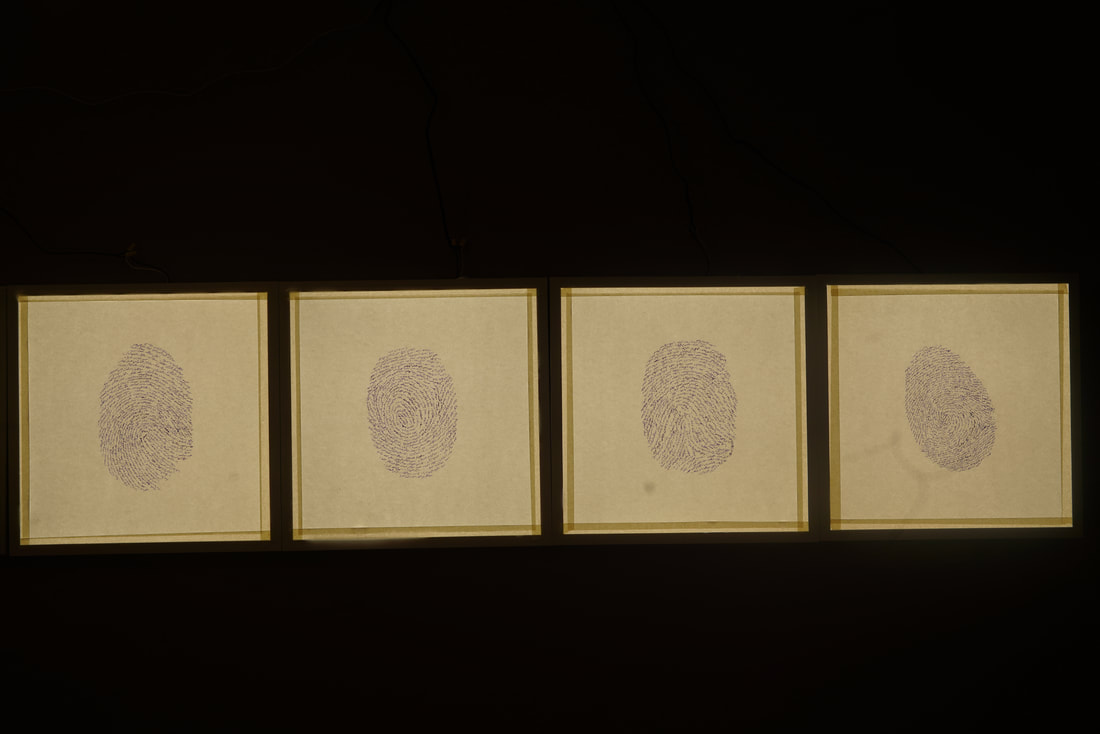

Manufactured Democracy, Ink on Paper and lightboxes, 2021

Geruk, Performance art, video, 2011